Buyer Beware: Active Investing

The perils of traditional active management

To support the publication and receive new articles directly to your inbox, please subscribe:

There are, broadly speaking, three different types of investing — active, passive and evidence-based.

Active investing involves trying to pick the right assets to buy and sell at the right time.

Passive investing entails tracking equity and bond markets and capturing market returns (less fees) as cheaply and efficiently as possible.

Evidence-based investing sits between the two, using passive structures whilst actively tilting portfolios towards assets with higher expected returns, based on the long-term market data (click here for more detail).

Historically, active investing has been far more popular than the other two methods; however, the rationale for using traditional actively managed funds is fundamentally flawed.

The Background

Typically, if you’re investing money, you’re doing so because:

You want the investment to grow in value.

You want to protect it against inflation.

You want to use the funds to help you live the life you want to live.

With investing, there are thousands of things you could do with your money.

Usually, you’re buying something with a view for it to grow and/or generate an income.

Typically, it’ll be shares in public companies, government/corporate debt, or property.

You can either do this directly or through a third party, such as a fund manager.

Active Investing

The idea of active investing is that you, or somebody you trust (e.g. a fund manager), are making conscious decisions to buy or sell assets at specific times, in specific ways, to generate some kind of outperformance against a chosen benchmark (e.g. S&P 500).

You/they will be making decisions about exactly what to buy and sell… ‘buying X is going to do better than selling Y’, and so on.

The decisions are being made with the intention to outperform the market - which is active investing in a nutshell; making conscious choices to buy and sell things at specific times in an attempt to generate outperformance.

Sounds good, right?

Wrong.

Whilst it may sound appealing, nobody has a functioning crystal ball to reliably predict the future and stay ahead of the curve.

And the last few years have rammed this home for us; there’s always something unexpected around the corner.

You only have to look back over the early 2020’s to see this in action:

COVID.

Ukraine.

Inflation crisis.

Hamas attacking Israel.

You can’t predict these things. We don’t know what’s going to happen. So, it’s nigh on impossible to consistently get active investment decisions right.

Market Timing

Market timing is the essence of active investing.

There are endless threads online about people discussing/selling courses on how to perfectly time investment markets (and, more recently, crypto markets!).

Market timing is guessing what the market, or an asset, will do next.

When something will go up, or down in value.

Armed with these guesses, you can make bets on when to buy or sell. When to take profits or benefit from opportunities that aren’t available to passive or evidence-based investors.

The issue is:

You’re guessing (never a great strategy for an important life choice).

You have to be correct twice.

You have to buy at the right time and sell at the right time. How often can you correctly guess two coin flips in a row?

Not many…

And a two-sided coin is much simpler and more predictable than investment markets/other humans.

Case Study: COVID

Remember 2020? More specifically, March 2020?

Good times…

The COVID panic of 2020 is a perfect example on the futility of market timing.

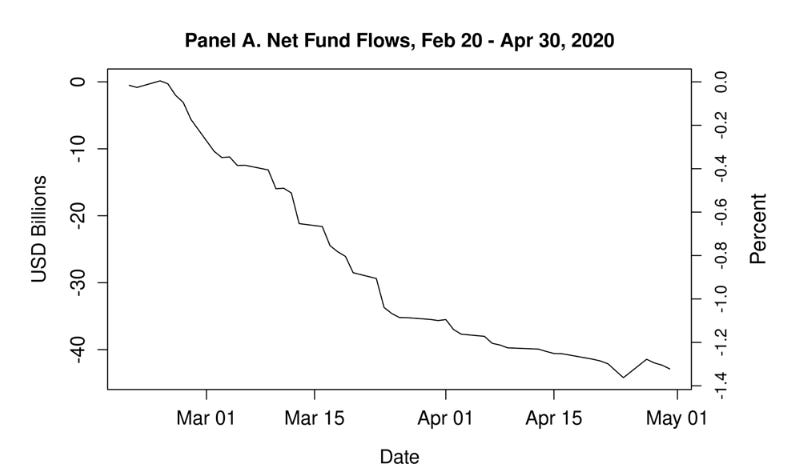

The global stock market steeply declined through early March, causing investors to pull billions of dollars out of the market - fleeing to the ‘safety’ of cash:

Many people (investment managers and pundits included) were, quite understandably, working on the assumption of a prolonged downward trend in the markets.

Quite a ‘safe’ assumption to make at the time, right?

Wrong.

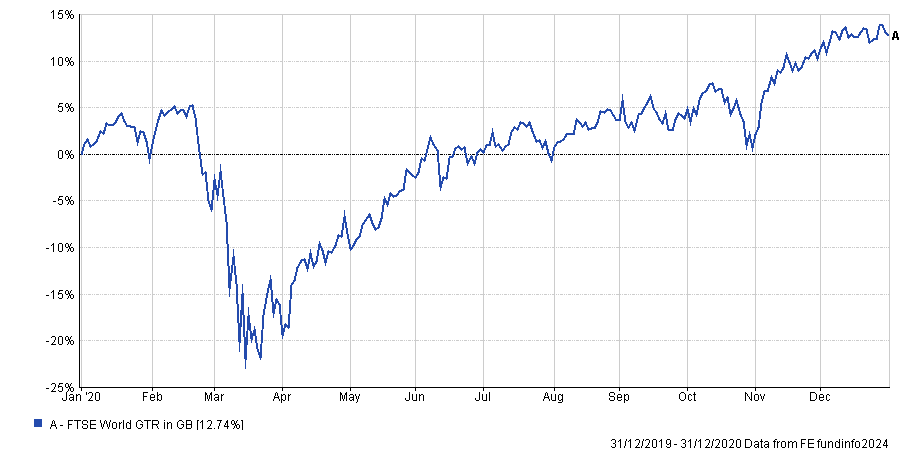

The bounce back from the lows of March didn’t take long and a strong recovery was underway - who could’ve predicted 2020 would be a positive year for the markets?!

How many ordinary folk had their financial futures destroyed by such an ill-timed active decision?

I was working at HL at the time and was repeatedly told by customers selling during the crash that they would ‘sell now and buy back in when the market recovers’…

A.K.A, selling low, buying high - which is a recipe for financial destruction.

(HL is an execution-only service, so I couldn’t offer an alternative option… it was a painful experience!).

Many of them would’ve remained in cash ever since; allowing it to be incinerated by inflation, rather than being subjected to the temporary declines of the global investment markets:

With an evidence-based or passive approach, there would’ve been no active decision to sell out of the market.

The message would’ve been to ‘hold the line’, and we can see how that’s paid off!

Active Fund Management

You may make think that employing a professional would increase your chances of success, but professional active fund managers encounter the same challenges as the rest of us.

They can be well-educated and work extremely hard...

They can have well-resourced research teams...

They can paint really engaging pictures...

They can be well-connected people...

But, they just cannot predict the future — the same as everybody else!

And all these bells and whistles comes with a cost.

So, not only do they have to consistently outperform the market, they also need to provide sufficient returns above and beyond the outperformance of the market to account for their high fees.

Over a long enough timeframe, nearly all will underperform:

End result = you’re overcharged for underperformance.

Now, for balance, some do get it right…

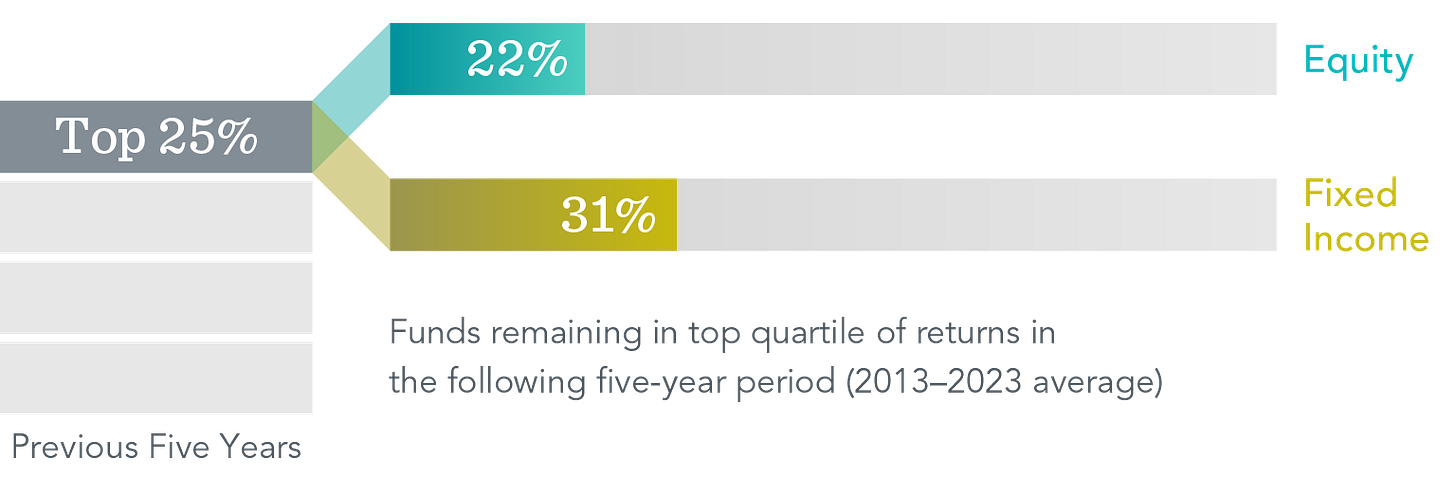

But what we tend to see when looking at fund groupings in any given year, or over a few years, the funds in the top quartile won’t be there when you look in the next couple of years.

Only a small percentage of funds in the top 25% over a 5-year period will still be there 5 years later:

Yes, some do outperform, but how do you select which funds are going to outperform in advance and then jump ship to the next one before the returns dwindle?

It’s almost impossible.

You’d have better luck finding a needle in a haystack.

Buyer beware.

What’s The Alternative?

Click here to find out.

If you enjoyed the article, please consider sharing it with someone else who’d also enjoy it or more widely on social media, it really helps:

Oh, and don’t forget to subscribe, so you can get future articles directly to your inbox!

Thanks for reading,

Tom Redmayne

Cambridge-Based Financial Planner

This article is based on a video by my colleague, Chris Wallsgrove, which you can watch by clicking here.

The value of investments can go down in value as well as up, so you could get back less than you invest. It is therefore important that you understand the risks and commitments.

This is not personal advice based on your circumstances.

All views are my own.